BlankSpace Publications

A Special Gravity: Photos as Objects of Memory

We can pinpoint the exact time that physical printing largely receded: when smartphones became ubiquitous. The last personal-use physical photos I printed out were from the mid 2000s, before I bought my first a digital camera in about 2005. I did print out digital photographs for exhibitions, but not really for photo albums. As soon as I acquired that digital camera, most of my post-2005 pictures remained trapped on my computer. When I look back at some of those physical photos now, it seems like a different era, even though we were well into the digital and Internet age. How can 2005 seem so long ago?

As a Gen-Xer, I am old enough to remember a time of pre- and post-Internet. I'm wondering if the paradigm shift of the millennial generation will be remembering pre- and post-printed photos. Millennials will regale their children with tales of a time before the digital image, when they had to drop physical film off at a photo lab to have it developed.

My uncle, who died prematurely of cancer in 2010, spent two years in Kenya, Africa, in the 1980s teaching mechanics in communities and at the University of Nairobi. Recently, I've been sifting through a bunch of the physical projector slides of his experience. These are the only images that remain of his trip, as our family cannot locate the negatives, despite our best efforts of scouring the farmhouse where he lived. Transferring these slides to digital format has necessitated purchasing on old slide projector and physically taking a picture of the projection on the wall. (I’m sure that there are better modern conversion techniques, but I prefer the laborious methods.)

I often wonder how much his impact resides in (even haunts) the community he helped to this day. I wonder how many people’s lives he changed for the better, and how many still think of him. This is precisely how people haunt environments, and how the specters of the past become even more haunting when reified in a photograph. Because of the high mortality rate in the communities he served, some of the children and individuals I see smiling at me from the stasis of these images have likely passed. And yet there are the ripple effects of the undoubtedly positive impact he made with his presence. How far does that ripple extend?

As I view the slides (projected on my basement wall) of his time in Kenya, I am reminded, too, of how he left a fairly comfortable life in Canada and immersed himself in a dangerous environment. There are many questions I would ask were he alive today. These are the origins of family myth-making. This is the moment when family members piece together the past through the objects they possess, and then fill the lacunae with their own speculations. Objects become heirlooms that lose their identifiable meaning the more they are removed from their origins.

My uncle was teaching a class at the University of Nairobi when the school was attacked by a terrorist group (I’m not sure which one). The school was evacuated and swept for dangerous materials (bombs, for example) before classes were to resume. When he returned to his classroom days later, he found a machete on his chair, perhaps forgotten by the attacker, with a handle bound in some type of skin (a common practice of terrorist groups in that region). He was able to pack it in his carry on when he returned home (imagine that—he was able to bring a machete on a plane back in the 1980s!). I have it to this day, and it is a very haunting family heirloom. Heirlooms can come in the strangest forms.

* * *

As Elizabeth Edwards argues in “Photographs as Objects of Memory,” “Photographs express a desire for memory and the act of keeping a photograph is, like other souvenirs, an act of faith in the future. They are made to hold the fleeting, to still time, to create memory” (332). Indeed, a photograph “projects the past into the present,” and even ushers “the dead among the living through the inscribed image” (332).

Our relationship to photography has certainly changed with the proliferation of smart phones and social media, where digital photos can be snapped and archived in cyberspace almost instantly. And yet the idea that even digital photographs haunt the present with mementos of the past is demonstrated through the pervasiveness of Facebook memorial pages (see the article “Facebook introduces 'memorial' pages to prevent alerts about dead members” in The Telegraph). While such pages offer a way for friends and family to honour the memories of passed loved ones, the departed linger in the ether of the web, absent but still hauntingly present. Such memorials, bolstered by the powerful specter of photographs that comprise an ethereal body, are the ghosts of our modern times.

Most families possess as treasured objects the ubiquitous family photo album. Many of these albums contain images of celebratory moments: graduations, weddings, birthdays and holidays. They also archive the past and, thereby, bring the dead among the living—deceased grandparents and relatives, treasured pets, and so on—to express a family narrative, a familiar story, or perhaps an enigma. As Edwards argues, physical photographs, the kind processed in darkrooms and developing trays, have a specific kind of impact through their materiality. They are physical, externalized objects of memory that have a “specific gravity” that can even make “the recently dead more precious than that of the living” (332). In a sense, photographs reify the past through the invocation of memory.

By contrast, digital photos that remain imprisoned on smartphones, while having their own gravity, simply don’t have the same magnitude as their physical counterparts. How many times has a friend or family member shown you a photo on their smartphone, only to discover that they had taken the exact same photo about ten times to get the right angle and lighting? Taking ten of the same photo does not imbue exceptionality. There is less intentionality to it; less urgency; less necessity. What’s more impactful: seeing one photo of your great-great grandparent, or one thousand? I don't mean to sound like a cantankerous luddite, so suffice it to say that perhaps it's the scarcity of the physical photo—the pressure to get it right the first time so as not to waste film—that makes it exceptional. It makes such moments less ephemeral.

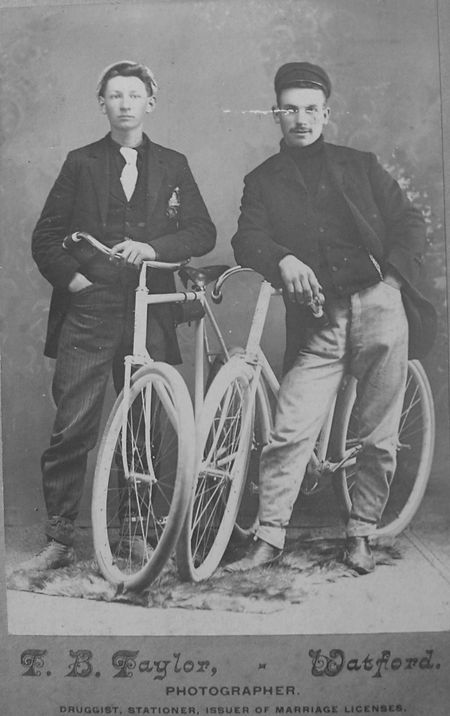

A few favorite photos I took while snooping through my grandparents’ house like a relic hunter are what you might classify as readymade ephemera. They are photos of advertisements for long-shuttered local businesses, back in a time when one could be a “Photographer, Druggist, Stationer, and Issuer of Marriage Licenses.” Some of these photos were never meant to be preserved—they are akin to the flyers we frequently throw into the recycle bin as soon as we receive them—but they nevertheless offer a ghostly vignette of a very different past, and I’m glad they survived long enough for me to steal a shot. However, while some of these found photos were distributed as advertisements, likely as examples of what the “Photographer, Druggist, Stationer, and Issuer of Marriage Licenses” could produce, others were legitimate family photos where members had gathered, dressed nicely, done their hair, and posed with austere countenances for the sake of preservation. (Ironically, what I have offered here are photos of photos, digital versions of that physical exceptionality, and I gave some of them very uninspired names: “Sassy Gentlemen with Bikes” and “Distinguished Man with Chair.”)

The haunting nature of such photos is not necessarily their existence as ephemera haphazardly encountered among heaps of disposable items—although such jarring encounters play a part in their ghostly nature. It’s the trace of human agency, of intentionality, of being present in a particular moment. These individuals stood to be photographed at a particular time in a particular place—there was travel involved, objects to be staged, poses to be manufactured, homes to return to, the day’s business to be completed. These people are long dead. What’s left stares out at us with somewhat apathetic and dead eyes as if to say “Life is ephemeral.” Like the store flyer we relegate to the recycle bin, everything eventually experiences an analogous fate.

Think about the objectness of photographs for a moment. What is it about their physical presence that invokes this “specific gravity”? What is it about their physical objectness, or perhaps their enigmatic nature, that haunts the present with mementos of times passed? These photographs could be family photos, photos in a gallery or museum, or even abandoned photos you might find at a junk shop or flea market. The point is that they are physical, artifactual. They express the past to the present with their haunting aura. Even seeing an image of myself as a child makes me think of the many manifestations we adopt as life progresses. We are constantly leaving ghosts of ourselves behind. I imagine that my child ghost, captured in those photos, lives at the county dump alongside my childhood objects: discarded clothes, toys, forgotten stories I wrote. One can only hope that those objects burned easily, or live far below the surface, away from the vermin and larvae that burrow holes in such tapestries.

To conclude this stream-of-consciousness discussion on the gravity of photography as artifacts, below you will see three photos of dogs. One is digital and the other two are physical. The digital photo is of my current dog (a golden retriever); the next is of my father’s first dog, named Shadow—a fitting name for a ghost dog (circa 1958); the third is a family photo, circa 1925. It’s a family portrait in which the farm dog obviously interjected as the family stood for a posed portrait. Rather than shoo the dog away, they took the picture anyway. I included these animal photos for a few reasons. First, taking a photo of a farm dog in a time of expensive photo processing speaks volumes. Such images demonstrate the softer moments imbedded in the more grave, serious business of life—the bits of humanity and emotion behind the usual austere faces staring back at us from older black and white pictures. These photos have a specific gravity that represents the counterforces within farm life and the contradictions we must reconcile in our daily existence.

Animals, both living and deceased, impact our daily lives and greatly influence the people we become. In some ways, people live their lives in chunks based on their pets. When I was a boy, my first dog was also a golden retriever, named Buffy, who met a tragic end (farm accident). This period is referred to as my Buffynean Period. After that there was Bandit, who also met a tragic end (car accident). This is my Banditean Period. Then there was Tucker (cancer)—my Tuckerean Period. And now there is Stella (ongoing)—the Stellean Period. They have all been a part of my evolution into adulthood.

These photos have a very specific gravity. It's not necessarily the emotion tied up in having animals. These images speak loudly to the paradox inherent in the operations of a farm and the care we give to domesticated pets and livestock. Shadow, along with most of our farm dogs, met a tragic end typical to farm living (animal attacks, farm equipment accidents, etc.). Losing these dogs was just as impactful as viewing these ghosts in the photos, as they conjure memory linked to emotion, linked to geography, and linked to a specific place.

What so many of these photos reveal is a past to which we cannot return. The digital photos we take today will be a warning to the future. Photos of pets, birthday parties, and family gatherings become haunting to us because of the “simpler” times they represent. They remind us not to take anything for granted.

Ru-Ex

Rural Exploration.